The perfect egg

How to boil a 63 degree egg all the time, without any fancy tools.

We have all become accustomed and just openly accept the fact that GPUs (Graphical Processing Unit) are the bee’s knees for ML. While the results speak for themselves (most of the time), have you ever wondered, what makes GPUs and DSPs (Digital Signal Processor) (i.e. TPUs - Tensor Processing Unit) faster for ML calculations that CPUs (Central Processing Unit)?

What is about to follow is an in-depth and technical detail of the differences in hardware architecture and what makes certain hardware better at matrix multiplication operations (matmul ops), which are at the heart of ML.

We’ll also discuss the concept of Turing completeness and its relevance to these hardware architectures.

CPUs are the general-purpose workhorses of a computer system. They are designed to handle a wide variety of tasks efficiently. CPUs can perform operations such as addition, multiplication, load, store, compare, and branch. They are designed to execute a series of instructions, one after the other, in what’s known as the Von Neumann architecture.

CPUs are particularly good at tasks that require high single-thread performance, including complex decision-making tasks that involve a lot of branching (if-then-else) decisions. They have sophisticated control units that can predict which way a branch (an if-then-else decision) will go before it is executed, a feature known as branch prediction. This allows the CPU to fetch and decode instructions ahead of time, reducing delays and improving performance.

CPUs also have a hierarchy of memory caches (L1, L2, L3) that store frequently used data close to the processor cores, reducing the time it takes to access this data. This is particularly useful for tasks that involve a lot of data reuse.

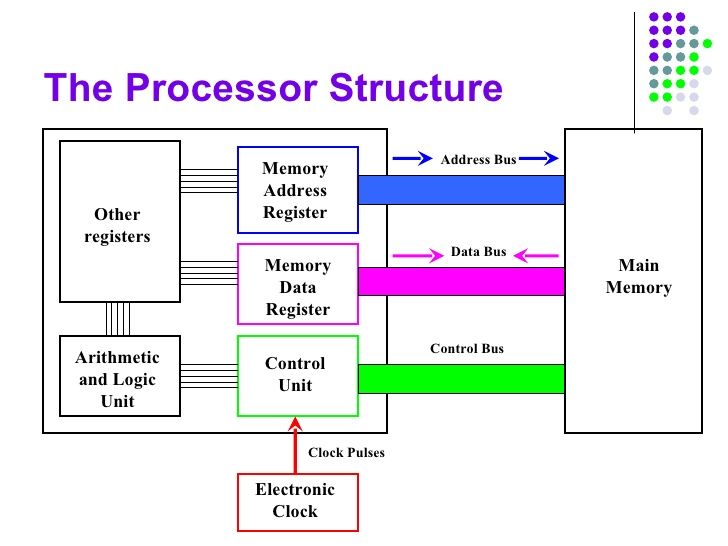

A CPU consists of several key components or functional units:

Arithmetic Logic Unit (ALU): The ALU performs simple arithmetic and logical operations. Arithmetic operations include addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. Logical operations include comparisons, such as determining if one value is equal to, less than, or greater than another.

Control Unit (CU): The control unit manages the various components of the computer. It reads and interprets instructions from memory and transforms them into a series of signals to activate other parts of the computer. The control unit also manages the flow of data within the system.

Registers: These are small storage areas that hold data that the CPU is currently processing. There are various types of registers, including data registers for holding numeric data, address registers for holding memory addresses, and condition registers for holding comparison results.

Cache: This is a small amount of high-speed memory available to the CPU for storing frequently accessed data, which helps to speed up processes.

Buses: These are communication systems that transfer data between components inside a computer, or between computers.

Branching: This is a type of instruction in a computer program that can cause a computer to begin executing a different instruction sequence and thus deviate from its default behavior of executing instructions in order. Branching can be conditional (executed if a certain condition is met) or unconditional. Branching comes in handy for controlling the flow of programs (especially loops), it allows for optimisation by skipping certain sections of code that might not be relevant based on certain conditions and overall provides flexibility w.r.t. the execution pathway of the program.

Comparison: CPUs use comparison instructions to compare two or more units of data. The results of these comparisons are often stored in a special register, and can be used to influence program flow via branching.

Storage: CPUs interact with memory to store and retrieve data. This can involve various levels of memory, including registers, cache, RAM, and persistent storage like SSDs or HDDs.

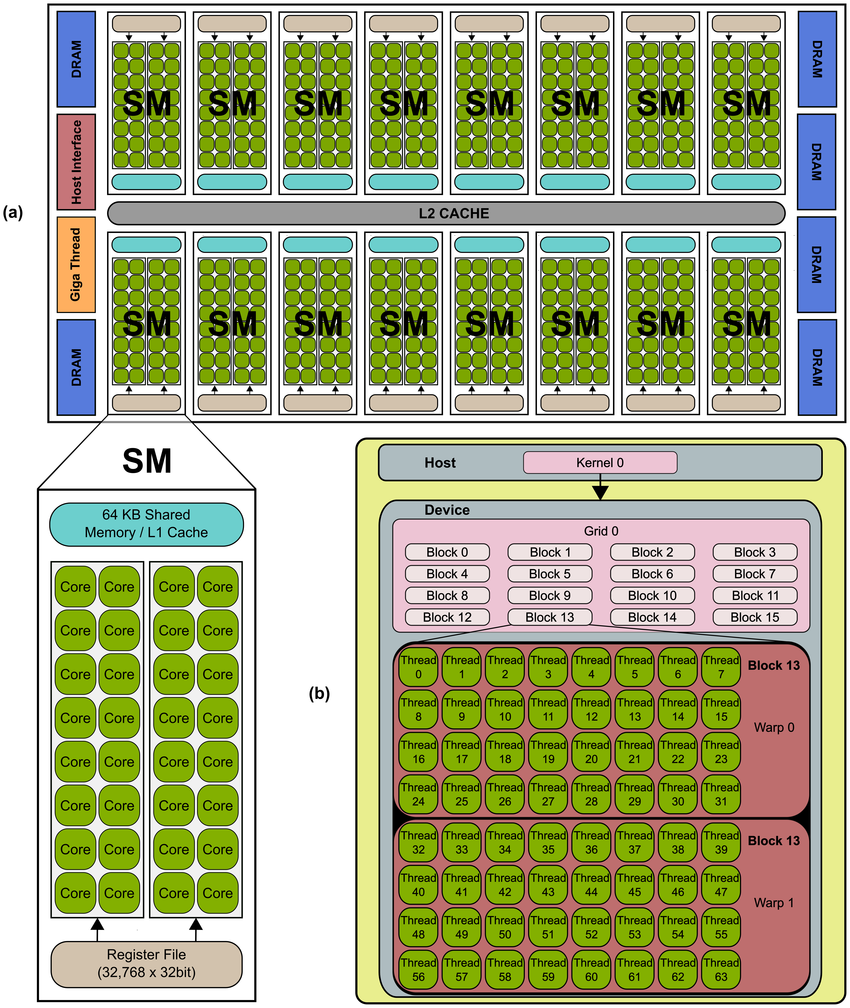

(Typical NVIDIA GPU architecture. The GPU is comprised of a set of Streaming MultiProcessors (SM). Each SM is comprised of several Stream Processor (SP) cores, as shown for the NVIDIA’s Fermi architecture (a). The GPU resources are controlled by the programmer through the CUDA programming model, shown in (b).)

GPUs, on the other hand, are designed for tasks that can be performed in parallel. They originated as specialised hardware for rendering graphics, a task that involves applying the same operations to many pixels at once. Over time, GPUs have evolved into more general-purpose parallel processors.

GPUs can also perform operations such as addition, multiplication, load, and store, but they are not as good at branching and comparing as CPUs. While they can technically perform these operations, they do so much more slowly. This is because GPUs are designed to execute the same instruction on multiple data points at once, a concept known as Single Instruction, Multiple Data (SIMD). Branching disrupts this parallelism, leading to performance degradation.

However, GPUs excel at tasks that involve performing the same operation on large amounts of data. This makes them particularly well-suited for machine learning tasks, which often involve operations such as matrix multiplication on large datasets.

Streaming Multiprocessors (SMs): In Nvidia GPUs, for example, the core processing is done in SMs. Each SM contains a number of CUDA cores (similar to ALU in a CPU), which perform the actual computation.

Texture Units and Render Output Units: Texture Units and Render Output Units are primarily designed for graphics rendering, but they can also play a role in certain types of machine learning computations, particularly in the context of deep learning.

Texture Units: In the context of machine learning, Texture Units can be used for their ability to efficiently handle multi-dimensional data. For instance, convolutional neural networks (CNNs), which are commonly used for image processing tasks, operate on multi-dimensional data (tensors). The operations that Texture Units perform, such as interpolation and mipmap generation, are similar to some of the operations in a CNN, such as pooling and convolution. Therefore, some of the capabilities of Texture Units can be leveraged to accelerate these operations.

Render Output Units (ROUs): ROUs are less directly applicable to machine learning computations. However, their ability to handle large amounts of data in parallel can be beneficial in a machine learning context. However, from my research, it didnt’t seem that they were being utilised to a significant extent for ML workloads.

Memory: GPUs have their own dedicated high-speed memory, separate from the main system memory.

Parallel Processing: GPUs are designed to perform many operations simultaneously. This is particularly useful for graphics rendering, where the same operation might be performed on many pixels or vertices at the same time.

Texture Mapping and Rendering: These are specific to graphics processing. Texture mapping is the process of applying an image to a graphics surface, and rendering is the process of producing an image from a model.

Compute Operations: Modern GPUs can also perform general purpose computation. They can execute thousands of threads concurrently, making them well-suited to tasks that can be broken down into many smaller ones, such as machine learning, where the same operation might be performed on many data points.

Parallelism: The main difference between a CPU and a GPU is the way they handle tasks. A CPU consists of a few cores optimised for sequential serial processing, while a GPU has a massively parallel architecture consisting of thousands of smaller, more efficient cores designed for handling multiple tasks simultaneously.

Memory Architecture: CPUs have a small amount of fast cache memory, and a larger amount of slower main memory. GPUs have a large amount of fast memory, which is crucial for tasks that require a lot of data to be loaded at once.

Latency vs Throughput: CPUs are designed to minimise latency, the time it takes to complete a single task. GPUs are designed to maximise throughput, the amount of work done per unit of time, even if each individual task takes longer to complete.

Machine learning tasks often involve performing the same operation on large amounts of data. For example, training a neural network involves repeatedly multiplying matrices and applying the same function to multiple data points. These are tasks that can be easily parallelised, which is why GPUs, with their many cores and high memory bandwidth, often outperform CPUs for machine learning tasks.

Furthermore, machine learning tasks often involve large datasets that don’t fit into the CPU’s cache. This means that the CPU often has to fetch data from the slower main memory, which can be a bottleneck. GPUs, on the other hand, have larger amounts of high-speed memory, which can reduce this bottleneck.

That being said, not all machine learning tasks are best suited to GPUs. Tasks that involve a lot of branching, for example decision tree algorithms, might be better suited to CPUs. Similarly, tasks that require low latency might be better suited to DSPs.

Digital Signal Processors (DSPs) are specialised microprocessors designed specifically for processing digital signals. They are optimised for operations such as addition and multiplication, but unlike CPUs and GPUs, they can only perform static loads and stores. This means they can only fetch and store data from locations that are known before the program runs.

DSPs are designed for high throughput, low latency, and real-time signal processing tasks. They often have features such as hardware multipliers, circular buffers, and zero-overhead looping that make them efficient at these tasks. DSPs are used extensively in fields such as audio and video processing, telecommunications, and digital image processing.

In the context of machine learning, DSPs are well-suited for tasks that involve a lot of matrix operations and require low latency, such as real-time voice recognition or video processing.

Turing completeness is a concept from the theory of computation. A system (like a computer or a programming language) is said to be Turing complete if it can simulate a Turing machine, a theoretical machine that can solve any computation problem given enough time and resources.

In practical terms, a Turing complete system can perform any computation that can be described algorithmically. This includes not only simple operations like addition and multiplication, but also more complex tasks like making decisions based on comparisons (branching) and executing different code paths based on those decisions.

However, the ability to perform any computation comes with a cost. Turing complete systems like CPUs need to include complex hardware and software mechanisms to handle the full range of possible computations. For example, CPUs include hardware for branch prediction and speculative execution to speed up decision-making tasks. These mechanisms can be quite complex and require a significant amount of resources, including transistors, power, and design effort.

In contrast, DSPs and to some extent GPUs, are more limited in the computations they can perform, but they can be much more efficient at the tasks they are designed for. For example, DSPs are designed to perform a limited set of operations (like addition and multiplication) very efficiently. They can’t perform arbitrary load and store operations or make decisions based on comparisons, but they don’t need to include the complex mechanisms that CPUs do to handle these tasks.

In the context of machine learning, many tasks can be broken down into a series of simple, parallelised operations. For example, training a neural network involves a lot of matrix multiplications, which can be performed independently and in parallel. These tasks don’t require the full computational power of a Turing complete system, and can be performed more efficiently on hardware that is optimised for these specific operations.

By removing Turing completeness from the hardware, we can design systems that are simpler, more efficient, and more suited to the specific tasks we need to perform. This is the idea behind specialised machine learning hardware like Google’s TPUs, which are designed specifically for the types of computations involved in neural network training and inference.

Further reading:

Further listening: